The Bavarian Freedom Initiative

Allow me to introduce myself…

My name is Mathilde Fahrbauer. I was born in Munich on March 24th1912. I grew up in Schwabing and attended the Kerschensteiner Academy in Franz-Joseph-Street until 1932. Here school girls could earn the higher education qualification diploma. In this way I was able to attend lectures in architecture at the Technical University of Munich from 1932 to 1939 – despite some early issues as a woman alone among men. During this period I served in the Reich Labor Service. In 1939 I found employment as a construction draftsperson for an architectural agency in Rottach-Egern. In 1944 the general mobilization of all civilians deployed me as secretary to an interpreter unit in Munich.

Even if this story sounds plausible, I remain a fictional figure. Nevertheless, I am honored to escort you through the last months of World War II in Munich and to tell you about the Bavarian Freedom Initiative, which really did exist…

Danziger Freiheit

The name change of Feilitzsch Square, where Mathilde Fahrbauer lived, to Danziger Freiheit was hardly noticed by her. During December of 1933 she was falling in love with Ottheinrich Leiling, whom she met drinking punch at the square. Everyone called him Ottheinz. He was only two years older than she and midway through his law studies. Even though her mother was nervous about the change in government, Mathilde was confident that the National Socialists would not rule long. Governments had been changing hands often enough. Mathilde was waiting for Ottheinz’s reply to her letter – or possibly a phone call, since she could use the neighbor’s phone. Her father felt that they needn’t join in on every trend. The radio alone was making enough noise.

In August of 1939 Mathilde was beginning her professional career in the architectural agency in Rottach-Egern, and even she realized that Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP would not readily give up their grip on power. There were varied opinions in her circle of friends. Most of them felt comfortable with their roles in the Reich Labor Service, in the Nazi Student Alliance and with the new society, which was apparently lifting Germany to better international recognition. Others were apprehensive about the enforced conformity and militarization, yet they participated where they had to.

Mathilde experienced one turning point in 1934 when her communist uncle Ludwig Ficker fled to Switzerland. Many of his comrades and friends had been interred in the new concentration camp in Dachau. Rumor had it that conditions were quite cruel there. The neighbors with the telephone were forced to move. They were Jews, but no one realized this fact until the Nuremberg Race Laws of 1935. The family of six moved to a small apartment in the Milbertshofen district. Their grocery store was given to an Aryan businessman. Early contact faded in the late 1930s when Mathilde heard that the family had been relocated in the eastern territories. Rumors also floated regarding these mass relocations. There were stories about shootings and work camps. These sounded so incredible that she wasn’t sure what to believe.

The Munich Interpreters

Mathilde was able to remain in touch with her former love, even though Ottheinz married another woman, whom he had met during studies in England. Ottheinz had been deployed as English interpreter just two years after the war began, which for Mathilde in Rottach-Egern was only marginally noticed. In the early 1940s interpreter units were organized by the army. Their main task on the front focused on communication with the civilians and translating in the POW camps while regulating the mail to the foreign prisoners. In spring of 1943 Ottheinz returned to Munich from his service in occupied Holland. He now gave English lessons to other soldiers. Even though the early confidence of victory was dampened by the German retreat from Stalingrad, the regime’s political and military leaders were certain that they would continue to need more linguistic experts.

At the end of July 1944 Mathilde was forced to serve on “tasks essential to the war effort” as part of the so-called general mobilization. Through references in higher military positions as well as the contact through her former love, she was able to receive a position as secretary in the Munich interpreters unit.

A good friend of her parents, Dr. Otto Leibrecht, stayed in Switzerland for Christmas 1944 following a business trip because he feared for his life in Nazi Germany. The Fahrbauers were afraid that his visit with them before this trip might somehow come out. Leibrecht had asked them to take care of his wife and children in an emergency.

By the beginning of 1945 several members of the interpreters unit sensed the closing curtain and cautiously started to hint at their doubts about the regime. Others apparently trusted the government slogans and retained their unshaking belief in the Führer. Mathilde often noticed Ottheinz Leiling vigorously debating with his colleagues Rupprecht Gerngross and Leo Heuwing while working in the interpreters’ office. By chance she learned that they maintained contact with Franz Sperr and his inner circle. He had been arrested with several others after the attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler in July 1944 and was now imprisoned in Berlin. In March and April of 1945 Mathilde noted that the three of them were meeting with officers from other units which the interpreters had not been involved with.

While talking with Ottheinz Mathilde let it slip out. In February1945 she had discovered a radio station broadcasting the situation in Germany in plain terms as announced by a man named Hagedorn. He asked that people prepare to save Germany through unconditional surrender. This would put an end to the National Socialist government and allow the country to recover under Allied control. After the war Mathilde found out that it was the friend of her parents, Dr. Otto Leibrecht, who fled Munich with reports about resistance plans there and provided the ideas for these broadcasts. These should undermine Nazi propaganda and give people the courage for resistance activities.

****

Radio excerpts

Sunday feature: “Attention, attention, FAB, Bavarian Freedom Initiative speaking”

On Sunday, April 26th 2015 the radio journalist Thies Marsen aired a segment in the series Zeit für Bayern” (Time for Bavaria). He travelled through much of Bavaria to put together this audio kaleidoscope of quotes on the FAB (Bavarian Freedom Initiative).

On Sunday, October 25th 2015 the informative contribution on the Munich Foreign Language Institute by Thies Marsen included a brief digression on the FAB, “Babylon in Schwabylon”.

***

Total War

During this time the Front was moving closer. By autumn of 1944 the enemy forces had reached the western border of the empire, and they were also approaching from the east. The local administrations announced plans with defense measures. This mobilization known as “Volkssturm” recruited older men and boys as a type of Home Guard. The regional administration received Volkssturm units with better trained recruits.

Life had become quite difficult in the severely damaged city of Munich: the attack alarms – usually at night – sent residents to the crowded, stuffy air raid shelters. They sat jammed together and could hardly breathe with the gas masks while praying for the all-clear signal. It was no longer possible to get food with the grocery stamps from the overcrowded stores. After long waits most items were sold out. One could procure some things through barter or connections. The numerous foreign workers and prisoners of war found it especially difficult to get food, even though they often had to work hard. Mathilde’s parents were lucky to have friends in the mining town of Penzberg, about 35 miles south of Munich. They now visited there more often.

Before working in the interpreter office Mathilde had never heard of the huge POW camp in Moosburg, about 35 miles away. She once accompanied the interpreter Leo Heuwing on an official trip in March 1945. There they met other interpreters, and on the return trip they visited his friends Robert von Werz and Ebba Ottow at the large estate Hirschau, which had unusual silo towers. Mathilde listened in on confidential conversations which didn’t sound logical to her. Part of the plan was to somehow connect with a tank unit in Freising and also to bring French POWs to the Schwabing district in Munich. One of the names dropped was the car repair shop of George Roedter, which was near the Fahrbauer apartment in Occam Street. Mathilde wasn’t clear on the situation. Her parents had left for Penzberg the week before, and she hadn’t heard anything from them since. This was not unusual with communication and travel being limited for civilians, nevertheless she was a bit worried. She also thought that the secretive manners of the interpreters was exaggerated. Since most people were concerned with their own problems, no one would notice.

Ten Point Program

In April Mathilde met one of her older cousins who quite directly asked about the interpreters. He was in Munich serving in the Volkssturm unit of the regional commander. He was apparently interested in suspicious slackers, who were of no use in his opinion. They would not be much help in defending the German Reich. Mathilde tried to wiggle out of the issue with some indefinite replies, but did not mention any of her observations. On one of the following days, April 26th 1945, she met Ottheinz in the office and told him about the strange questions posed by her cousin. Ottheinz was startled and took her into one of the small classrooms. He tried to cover things, but Mathilde was persistent until he finally told her: Since the failed attempt on the Führer’s life he had spoken with Heuwing and Gerngross about what might finally put an end to the war. They were waiting in vain for efforts to emanate from the group involved with the Reich Governor Franz Ritter von Epp. His adjutant Günther Caracciola-Delbrück had been in contact with them, but hadn’t communicated in a while. The radio announcements by this Hagedorn were speaking in clear terms, and that’s why they wanted to get involved by collecting as many weapons and as much ammunition as possible. In addition, Heuwing was able to use the Hirschau estate to connect with Freising and the POW camp in Moosburg, which she knew about. Two groups there wanted to participate. Yesterday they had been able to help two French prisoners of war escape from the camp. They brought them to an auto repair shop in Schwabing and planned to send radio messages on the Munich concept to the Allies. In addition, the commander of the large tank division in Freising, Major Alois Braun, was negotiating with them on how to engage his large unit to support them. They already had a name for this operation: “Freiheitsaktion Bayern” (Bavarian Freedom Initiative) – shortened to FAB. Things would begin as soon as the Allied forces were close enough to reach Munich within one day to support the initiative. Ottheinrich showed Mathilde a piece of paper with the Ten Points. A knock on the door made him quickly pocket the paper. Mathilde could not understand what he meant by an initiative, but she couldn’t pursue the matter since they would not meet privately in the near future.

The content of the note which Ottheinz had to hide so quickly:

***

The Ten Point Program of the Freiheitsaktion Bayern (FAB)

After the surrender of the Bavarian government, the ruling authority will transfer to the Freiheitsaktion Bayern. The FAB has formed a governing committee of 10 delegates for the individual regions.

This governing committee will conduct state business for Bavaria until the people of Bavaria have voted themselves a new constitution in a free election.

Specifically, the FAB guarantees that the following goals will be implemented during its tenure in office:

1. Eradication of the brutal rule of National Socialism. The Nazi regime has brought conditions which prove its inability to rule. The inhumane measures have broken the laws of morals and ethics, thereby forcing decent Germans to turn away with disgust. The government has resolved to destroy national-socialism, including its leaders and philosophy, to the very last entity.

2. Removal of militarism. The government will remove that militarism, which has driven Germany into several senseless wars. Notably in its Prussian form, it has brought endless hardship to all Germans. In its essence, militarism has never been a part of the Bavarian character. It remains the duty of the government to prevent any future military spirit from rising again, and proper educational measures for our young people are the answer.

3. Restoration of peace. The FAB will strive to conclude a lasting peace after attaining a ceasefire with the victorious opponents based on the efforts of reliable statesmen and the allied powers. Once liberated from the beastliness of the Nazis, the German people must again become an equal member of civilized humanity.

4. Fight against anarchy. The restoration of peace and order is the primary task for our ravaged country sadly in need of inner reconstruction. Therefore the government will employ all means to prevent irresponsible elements from taking advantage of the emergency situation to cause chaotic conditions.

5. Securing Nutrition. The most immediate duty for the government and the public after the irresponsible looting of our provisions by the Nazis lies in securing food. To prevent the impending famine caused by mismanagement and overpopulation in Bavaria, drastic measures are necessary. The government will equally and fairly distribute the limited groceries available. Profiteers and black market dealers will be punished with severe fines.

6. Restoring structured economic conditions. National-socialism has totally crippled the economy which must now receive the attention needed to utilize our country’s capacities towards reconstruction. The FAB has recruited the appropriate men from practical economic life in order to achieve this goal in harmony with the plans of the Allies.

7. Restoring the judicial system. To replace the Nazi criminal state, the FAB desires a legal system corresponding to the historical past of this country. This will primarily awaken the judicial consciousness of the German people and help cultivate civilized society. In accordance with true German legal traditions, the judge will once again receive the independence necessary to execute his office. In the future the police will limit themselves to duties expected of them.

8. Establishing social order. The government is obligated to create a satisfactory socialist state. It must be able to mediate any social tensions and contradiction which might arise. The citizen has the right to request assistance from the state when sick, aged or unemployed. In the modern state as viewed by the FAB, each person will find an appropriate position according to his/her skills.

9. Restoring the basic rights. The FAB guarantees the gradual restoration of freedom of the press and the personal freedom of assembly.

The FAB views Christianity as one of the most important state-forming factors and as the decisive concept in unifying and reconciling people. The religious institutions, the clergy and believers therefore stand under the expressed protection of the government. This does not affect the existing freedom of religion.

10. Restoration of human dignity. National-socialism has created the bureaucratic human of the masses – without an individual personality. The supporters of the FAB want to give back to every citizen their consciousness as free human individuals.

In addition, they are convinced that only by renewing the individual spirit can the renewal of the public spirit be attained. This basic principle inspires all their measures.

***

The Uprising begins

When Mathilde arrived to work the late shift the afternoon of Friday, April 27th 1945, there was a certain uneasiness in the air. At home she had listened to the Hagedorn station once again. He spent the whole time explaining that now was the proper time to attack. She was wet and cold on entering the barracks in Saar Street near the Oberwiesenfeld airport. On her way she had seen military units marching north apparently as preparation for defending Munich.

By 10 p.m. the interpreters were engulfed in bustling activity. They seemed to be getting ready to march. Suddenly Rupprecht Gerngross announced the plan: The national socialist government and military must be deposed. After concluding a ceasefire with the Allies, a governmental committee should direct Bavaria’s destiny. In order to include as many people as possible on this initiative, flyers and a newspaper have to be printed. The group placed their hopes on radio announcements made from the two stations they intended to occupy. Various groups in their division and in other military units took on tasks and responsibilities. Mathilde stood there lost. She should remain in the barracks along with reserves under Maximilian Roth.

“Attention, attention, FAB, Bavarian Freedom Initiative speaking”

Mathilde could not just sit there in the caserne and wait. As her excuse she told Maximilian Roth that she was tired and actually rode her bicycle home. Her intent, however, was to get warmer clothes and ride north through the English Gardens. She had heard that the Aumeister tavern was a meeting point for soldiers. She did indeed meet several interpreters there. The soldiers tried to convince her of the dangers and send her home, but she persisted.

They let her stay. Messengers and radio dispatches from various groups came in. Gerngross also drove by and stopped in briefly before heading north. Ottheinz was in a different car and luckily did not notice her in all the excitement. He certainly would have sent her home.

In the meantime it was just before 3 a.m., and everyone was waiting in front of a radio. About an hour earlier a crew had set out for the military radio station nearby in Freimann to make announcements to the population. And indeed at three o’clock the announcements started coming through in German, Italian, Hungarian, Russian and French:

Quotes in German and French from the Bavarian Radio archives/ Speakers: Dr. Georg Deyerler and Dr. Friedhelm Kemp

“Attention, attention, FAB, Bavarian Freedom Initiative speaking. You will now hear a proclamation for the French workers in Bavaria.

Hello, Hello! Attention, Attention! Listen, Listen! This is the Bavarian Freedom Initiative. We call on the French workers and all French people in Bavaria. Countrymen! [ ] The hour of freedom has finally come. The surrender will follow soon. Negotiations have begun. The Nazi gang has been destroyed. We hope you can participate in the events. French people, unite for a good cause, stand up and leave your work. Please maintain peace and order. Form groups united in passion, willpower and hope for peace, which our European civilization deserves. French people, the Bavarian people are waiting for you to support them in this heroic battle against Nazi terror, which has made them suffer so much these past 12 years. Attention, attention, you have heard an announcement to the French workers in Bavaria.”

Mathilde and the soldiers rejoiced. They hadn’t reckoned with things working out so quickly. The group with Kaspar Niedermeyr had been given the task of the announcements and was somewhat pessimistic. The transmissions for the announcements came from a studio in Ludwig Street in Munich, which meant, that a direct broadcast was not possible from the station. But they came well prepared and made things happen with some technical tricks.

Mathilde’s euphoria was quickly dampened. It turned out Ottheinz Leiling and Rupprecht Gerngross did not convince Reich governor Epp in time to offer the Allies a ceasefire on behalf of the insurgents. Therefore, they were now proceeding with him to Freising, where the older and higher-ranking director of the tank replacement division #17, Major Alois Braun, was to continue negotiations. He had also given the order the night before to Lieutenant Ludwig Reiter to occupy the big transmission station in Ismaning with the tank destroyer company #74. No messages from this group had come into the Aumeister. In the meantime the grenadier replacement battalion #19 under Lieutenant Helmut Putz arrived at the support center. They were scared and distressed. The 30 men had tried to storm the Central Ministry of Governor Paul Giesler in Ludwig Street. While attempting to enter the building there were problems as hand grenades hit them, according to one member of the small number who could escape to the north. No positive message came from the other group under First Lieutenant Hans Betz with 45 soldiers from the grenadier replacement battalion #61. They were not able to abduct General Siegfried Westphal as planned in Pullach. Instead they captured seven SS soldiers and occupied the Munich City Hall on their way back. Here they ran into the hated Nazi-profiteer Christian Weber, whom they also held in their truck. Mathilde went to look at the sheepishly clamoring, corpulent man. He was one of the most notorious enemies of the Munich people, not only for taking every opportunity to enrich himself. Leo Heuwing arrived at the Aumeister somewhat contritely. He was with 15 interpreters in Kempfenhausen and wanted to cut off General Staff Officer Stephani, but they could not locate him. At least they were able to put the communication system there out of commission. When the question rose about the group at the newspaper print shop in Sendlinger Street (Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten), no one had an answer. Hours later word came that the printing of the flyers and a newspaper for informing the public had been halted because contradictory messages regarding the copy came in.

The Chase begins

At 8 a.m. the soldiers who were gathered in the northern section of the English Gardens started off along the Isar River towards the large transmitting station in Ismaning. Mathilde had been sent home. Disgruntledly she got on her bicycle and rode back to the city. At home she immediately turned on her “people’s” radio. She was just able to catch the speaker reading off the tenth point of the FAB Program. It was also announced that the FAB was contesting the governing powers in Munich and that the public was encouraged to stand up against the National Socialists. Mathilde became uncomfortable because previous attempts to remove Nazi officials had failed. As tired as she was, nothing could keep her home.

She rode her bicycle along Saar Street back to the barracks. There she learned that the broadcasts from Ismaning had been transmitting since 6 o’clock that morning. She quietly rejoiced about the success at the second station which had a long range. Mathilde hoped that her parents could also hear the announcements in Penzberg. Suddenly she heard a thump and a handful of Volkssturm men appeared in the room and announced that they were occupying the barracks. Everyone in the room was immediately under arrest and should come along. Mathilde, Maximilian and two other interpreters were taken to the governor’s control post at the Central Ministry in Ludwig Street. There they were escorted by other Volkssturm men to the bunker complex. They were locked into separate little rooms similar to telephone cubicles.

Imprisoned in the Central Ministry

The room where Mathilde was locked in had a small window in the door through which she could observe the hectic activity of the Volkssturm men and the governor’s staff. The dogged zealousness in pulling all the levers to silence the insurgents made her shudder.

She was able to hear a radio nearby broadcasting speeches by the governor and then the mayor of Munich, Karl Fiehler. Now she was totally disheartened. Then she could suddenly hear the FAB station with the Ten Points. By 11 o’clock there were only announcements made by the Nazis. Mathilde broke out in tears; she was exhausted, but she still tried to get on her feet to see what was happening outside her door.

She recognized the dignified officer being led down the hall as Günther Caracciola-Delbrück. He was adjutant to the Reich Governor von Epp, who had just passed by. Not a good sign, since he was supposed to negotiate the ceasefire with the Allies. More noises came from Volkssturm men pushing a man in a grey smock down the hall. Mathilde later learned it was Johann Scharrer from city hall maintenance. He had been reported by Christian Weber for telling the FAB people where they could find him.

Shots in the Central Ministry

The door first opened in the afternoon and four men were led in. It turned that they had attacked members of the Hitler-Youth and Volkssturm in Obermenzing. Someone reported them, and they were arrested. Since it wasn’t clear if they could be heard, they only made small talk.

Mathilde could only speculate regarding the fate of Ottheinz and the others from the interpreter unit. Since they were not among the 20-some prisoners brought into the ministry that afternoon, she started to worry. She feared that they could not go into hiding fast enough and ended up shot. But she was so tired and couldn’t help but doze off, only to stir up with any noise. In the late afternoon the Volkssturm men led Günther Caracciola-Delbrück outside. Shortly thereafter gunshots rang out, and the Volkssturm men returned. The same happened with the man in the grey smock, whom one of the cell mates recognized as the city hall worker. Suddenly the door opened and the four from Obermenzing were led out one by one. Luckily they came back – with faces quite pale. They had been threatened, but nonetheless brought back. The night remained quiet in the bunker complex. Occasionally one could hear the brawling of drunken soldiers. The four inmates and Mathilde had a restless sleep in their cell.

Flight from the Central Ministry

On the morning of April 29th the five were again startled by crackling shots. Later an interpreter whispered to Mathilde in passing by that he was just set out to clean the driveway and saw the bodies of the interpreter Maximilian Roth and a supposed arms smuggler named Heinrich Gerns lying beside a lot of blood. In the afternoon new prisoners were brought in along with two men she had never seen before. Mathilde now realized with horror that the parents of Rupprecht Gerngross were being led past her cell door.

The whispering of the Obermenzing inmates tore Mathilde out of her thoughts. Their gestures and expressions indicated that she should stay close to them. There was hectic activity in the bunker complex as if the central ministry were being evacuated. The prisoners should come to the loading yard. Suddenly the guys from Obermenzing ran toward a car with Mathilde close behind. Before the Volkssturm men could notice, the car was driving away to the north. The guards were so busy with their own escape from the approaching Allies that they didn’t bother to chase the car. Out of the corner of her eye Mathilde saw a truck with four prisoners she did not recognize together with several guards heading south. Later on in 1945 their bodies were found in the Perlach Forest. The victims: Harald Dohrn and Hans Quecke, who had been arrested in Bad Wiessee, were shot even though they had nothing to do with FAB uprising. The other two were Johann Pohlen and Karl Rupperti, and there were no clues as to why and how they came into custody. The victims executed at the central ministry were placed on a truck and also brought to the forest area south of Munich.

During her time locked up in the central ministry Mathilde was not even asked for her papers. She felt relatively safe in working her way on side streets from Obermenzing to her parents’ apartment in Schwabing. She did not want to risk getting her bike from the Saar-barracks. She now had no intention of leaving the apartment. The few announcements on the radio were diffuse and unclear.

***

Film: “The Liberation of Munich/ April 30, 1945

On April 30th 1945 at 4:05 p.m. a legal counsellor of the Munich city administration surrendered City Hall to the officials of the 7th US Army.

***

US Soldiers in Munich

After escaping from the central ministry Mathilde did not dare to go outside. During the daytime she was happy to have their home-made canned goods, even though she had often joked with her mother about the process. If she stood on her toes in the attic and looked out the window she could see military vehicles in the distance, almost all of which were heading south. Surprisingly there hadn’t been any air-raid alarms in quite a while. She then took the risk of going outside for the first time in the night from Wednesday to Thursday, May 3rd 1945. She needed a first-hand look at the situation.

In the dark she stayed close to the buildings to make her way to the empty Leopold Street heading south. The piles of rubble from the bombed buildings were crudely pushed aside making things quite confusing. On reaching the corner of Franz Street at the Schwabinger brewery, she heard the steps of heavy boots and hid in a dark house entrance.

Luckily the three US soldiers did not see her. She had just read a poster stating that it was forbidden to be out at night. In addition, she had been frightened by the rumors of the past months telling about the bad things foreign soldiers did to Germans, especially German women. Scared and disturbed she quickly returned to the safety of her parents’ apartment. Never before had she felt herself so alone.

Offices of the FAB

On Friday morning, May 5th 1945, Mathilde decided to go outside again. Taking the smaller Clemens Street she headed toward the Saar-barracks. She finally wanted to get her bicycle. She made it through well enough, but several houses here had been hit and the apartments looked deserted. At the corner of Schleißheimer Street, just before the barracks, she heard the chugging of a motor getting louder. A US Army jeep approached.

Her first reflex was to run, but she knew she wouldn’t be fast enough. The two US soldiers eyeballed her and checked her papers. She stood there in her flimsy, dusty clothes. Her face was thin, pale and freezing. The soldiers furtively scrutinized her. They were freshly shaven and proper. One of them was black and had a glowing smile under his large, slanted helmet. The other was a stocky, dark-haired man with a charming dimple on his chin and a noteworthy profile. He spoke German with her without an accent. He asked where she was going. She felt more comfortable and described her situation: she was hiding and did not know what happened to her parents and the FAB activists. The soldiers had coincidentally heard the radio announcements, but did not know anything about the others. In parting the soldiers warned her to be careful because many Nazis were hiding in the city and there had been attacks on pedestrians.

Luckily, her bicycle was still locked to the flag pole at the barracks. A note was hanging at the entrance gate to the caserne:

Mathilde was in shock. She immediately biked to Schack Street at the Siegestor (victory arch). There she saw several familiar faces from the interpreter unit. She directly asked about Ottheinz and found out that he was okay. He had hidden himself in Munich until the Americans reached the city. He continues to search for higher Nazi officials still holding themselves up in Munich. He most likely is in the other office in the Wasserburg Street, but mentioned that he would stop in again. Mathilde decided to wait for Ottheinz in Schack Street. She hadn’t noticed that it was already dark outside. Because of the curfew she could not bike back to Schwabing. She tried to sleep on the couch, but was still in a stir. She had told others about the arrests and shootings in the central ministry. Other visitors to the office mentioned rumors about shootings out in the country, but nobody had any details.

Penzberg

After finally seeing Ottheinz again, Mathilde spent her time in the FAB offices. Nevertheless, she did not see him often. He was usually with the US military officials. For one thing, he was interrogated by the US secret service on the broadcasts by Hagedorn, who had played the role as a resistance station.

One late afternoon Mathilde’s parents appeared in the rooms on Schack Street. The Fahrbauer family was tearfully reunited. The parents had been so worried about Mathilde. They had gone through some bad experiences in Penzberg and heard that the unit Mathilde worked for was involved in the uprising in Munich. They couldn’t get through on the telephone and were so uncertain about the situation, which is why they did not immediately dare return to Munich. When the parents finally arrived in the city and found the apartment empty, they feared the worst. Then they found the note which Mathilde had carefully placed in the box in the hallway. That’s when they made their way to Schack Street.

After they all calmed down a bit, the parents distressingly related their experiences in Penzberg. Their friends and other town residents had listened to the FAB (Bavarian Freedom Initiative) announcements. The former mayor and other men quickly set out to prevent the blasting of the Penzberg coal mine. He also rounded up some forced laborers and went to their city hall to remove their Nazi mayor. The activists had scheduled a meeting for the Penzberg residents that afternoon. Mathilde’s parents also wanted to attend in order to find out how things might continue. But that never happened. After the governor again took over the radio programming and it became evident that the uprising had failed, things got restless in Penzberg. One army unit imposed a curfew and arrested the activists in the Penzberg city hall. The army soldiers took seven men to a forest sector, tied them to trees and shot them. Among the victims was a neighbor of the friends, with whom the Fahrbauers were staying. At night her parents were startled by loud motor noises. Through a window they were able to witness other insurgents being pursued. The Volkssturm men from Munich hanged six men and two women – one of whom was pregnant – in the streets of Penzberg. On their necks hung a sign stating “werewolf”. Nine other men were pursued: seven were able to escape; two of them were shot and survived, and a third perished from his wounds. Although a few days had passed before they left town, the residents of Penzberg were still quite traumatized: by the unspeakable savagery, their own helplessness, and the awareness of the informers, who had made a list of the participants in the uprising. The Fahrbauers also heard rumors of similar instances in other Bavarian villages, but they had no concrete details.

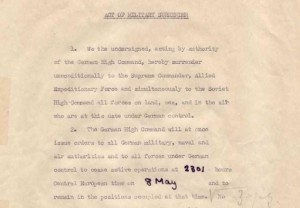

The Surrender of the German Armed Forces

At this time 70 years ago on May 8th at 11:01 p.m. the surrender of the German armed forces went into effect.

The picture shows Colonel General Alfred Jodl signing the capitulation document. Below is an excerpt from the paper which he signed.

Federalarchive/Military archive: Documents and description of the surrender in May 1945

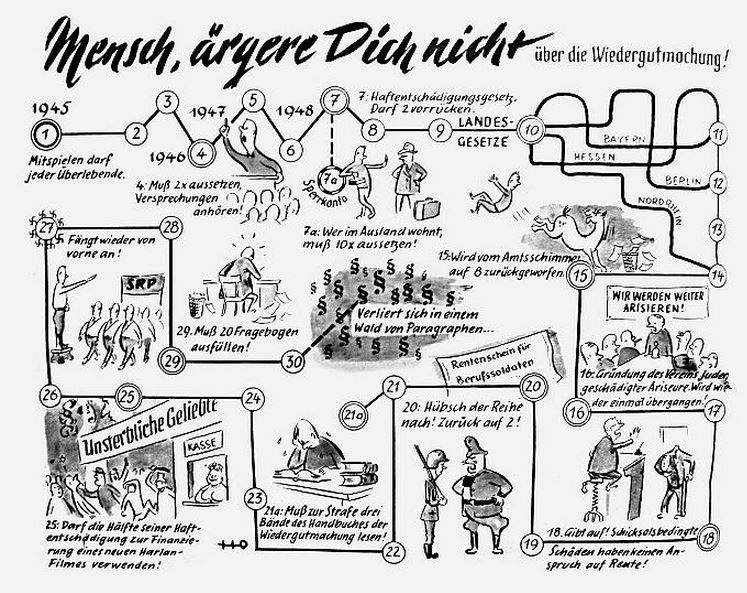

“Man, do not get upset…” (Pun on the game “Mensch ärgere Dich nicht”)

The surrender of May 8, 1945 finally sealed the official end of the war. Subsequently, the US military officials began to implement democratic structures step by step. The goal for these years lie in de-nazifying the German population down to street names and monuments. This so-called re-education included various tactics, newly-formatted newspapers and magazines patterned after American examples, and the radio station “Radio München”. The fanatic Nazi neighbor of the Fahrbauers, who had been training other SS soldiers in Dachau, now landed in the Dachau internment camp. His wife and the two children had to crowd into one room of their apartment. The other rooms served to accommodate refugees from the Sudetenland and East Prussia. At times there were sixteen people crudely quartered in the 60 square meters. The Fahrbauers also took in distant relatives. They came from Gablonz on the Neisse River. This Bohemian city was known for its glass and jewelry production. Soon they joined other former neighbors in moving to Kaufbeuern. That city district was later re-named New Gablonz and even continued with glass and jewelry production.

Otherwise there was a shortage of everything, especially groceries and construction materials. Nevertheless, the residents returned to the city and began to clean up and rebuild their houses. In the northern part of Luitpold Park a giant rubble mountain arose near the streetcar line.

The former forced laborers, POWs and survivors of the concentration camps were taken care of by the UN organization expressly established for them, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. These displaced persons, known as DPs, often had to remain in their camps and should ideally be transported back to their original countries. Rumors quickly spread regarding the treatment of the people who returned. Most notably those in the east encountered a hostile reception, which explains why most people chose not to return. Many Jewish DPs had spent a long time in camps because they had nowhere to go.

In the meantime the US officials introduced courts of arbitration. Everyone had to fill out a questionnaire regarding their involvement in the NS-government. Only those without criminal charges were allowed to work again. The courts used the questionnaires to sort the NSDAP-members into various crime categories.

During these proceedings evidence was collected which could charge people as well as exonerate them. For this reason numerous certificates of denazification were issued. To exonerate their interned father, the neighbors of the Fahrbauer family asked them for such a certificate. Father Fahrbauer acted as if he did not properly understand and chose to just avoid the neighbor. Those Nazis with lesser involvement were heard first. The point was to clear them quickly because workers were sorely needed. Those more heavily involved went on to the next phase, and, depending on the political climate, could slide into the harmless categories. In that way the charged neighbor was able to return as clerk in public service. He was on a committee which decided reparation payments for Jewish survivors in the 1950s. These applications generally wound up as lengthy proceedings, often for decades.

Caricature “Man, don’t get upset about the reparations”, from 1950 in the Jewish weekly paper (Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland).

A relative of the Jewish family next door, which had moved to Milbertshofen in the 1930s, stood at the Fahrbauer apartment door in the early 1960s. His lengthy investigation brought him to this address in Munich to find out something about his family. Their traces only led back to a transport list for the concentration camp Auschwitz. The old Fahrbauers were devastated and tried to scratch together some memories. So much had happened since then. Even the search for an old picture with the whole family of the former neighbors turned up futile.

***

Color movie: Postwar Munich (probably in May 1945)

***

Münchner Freiheit

Mathilde was quite fortunate to find work at Radio München. Among other things she broadcast critical reports about the difficult de-nazification process. One of her colleagues, the commentator Herbert Gessner, took this topic to a discussion with the special task minister responsible and soon lost his job. He went on to Berlin in the Soviet occupation zone. In 1946 Mathilde was also employed on the editorial board of the magazine “End and Beginning”. It was founded by a very young former soldier Josef Bautz and observed postwar politics critically. Thanks to several friends in the country and their garden plots, the Fahrbauers managed their grocery needs. But they also suffered during the extremely cold winter of 1946/47 and the consequences for nutrition in those hard times.

Things soon became calmer for the people involved in the Bavarian Freedom Initiative. For some strange reasons, the military government outlawed the FAB on May 17th. Somehow information leaked that the FAB was implicated for independently confiscating goods and was tied to a robbery with murder. Some had nevertheless been able to receive identification papers from the Munich head mayor.

In December 1946 the city decided to rename the former Danziger Freiheit, which after the war was called Feilitzsch Square again. The new name of Münchner Freiheit should commemorate the Bavarian Freedom Initiative and its activists. Mildred’s father thought it was a stilted name. That is why he continued to say Feilitzsch Square and was understood. He would also chuckle to himself when someone actually said “Münchner Freiheit”. He then acted as if he didn’t know where that might be.

Related Activities and Fatalities

Alois Braun and Mathilde occasionally met for coffee. He had commanded the tank division in Freising which also participated in the FAB uprising. He was now working in the cultural ministry.

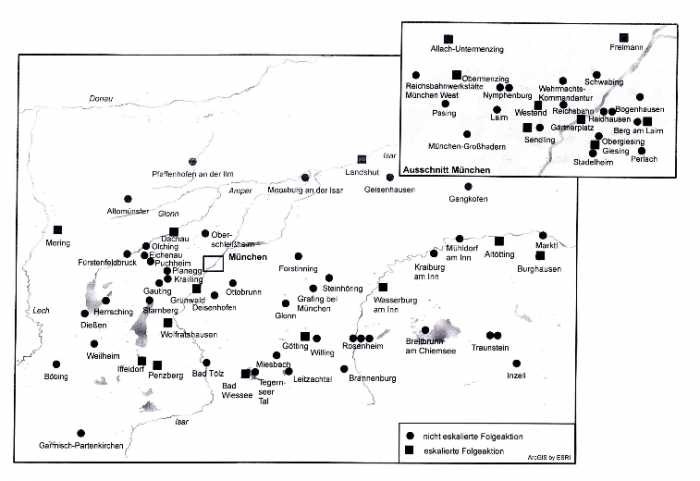

In an article in the newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung he called for an archive to be established expressly for reports about the resistance against the Nazi regime. Many accounts came in, not only from the FAB activists, but also from other groups. Like many concepts in the postwar period, this archive only existed for one year. These reports and the first court proceedings now documented the various events in southern Bavaria after the FAB announcements from stations on April 28th 1945. Motivated by these announcements, almost a thousand people in 78 locations throughout Bavaria made efforts to act against Nazi leaders locally and to prevent more defensive measures. They thereby resisted the morale-boosting slogans and final-victory propaganda of the Nazis by raising white flags, clearing away tank-traps or pointing out Nazi sympathizers. Similar to the situation experienced by the Fahrbauers in Penzberg, other towns also witnessed the escalation of violence once the governor of Munich and Upper Bavaria was heard on the radio and it was clear that the FAB uprising had failed.

In Allach-Untermenzing, at Gärtner Square in Munich and in Sendling FAB sympathizers shot supporters of the NS regime. In 16 additional cases NS henchmen killed 54 people, who had followed the call of the FAB announcements:

In Munich’s Giesing district an SS soldier shot a man because he was hanging a white flag out of the window. In the Westend district two men were almost hanged for similar actions, but they narrowly escaped death because the rope tore. Police shot one citizen from Mering while he was fleeing. He was spreading the word about the freedom initiative and was taken into custody. In Dachau the city hall was occupied, and a shootout ensued killing seven men. SS soldiers hanged a man in Landshut because he raised two white-blue (Bavarian) flags. In Altötting five suspected insurgents were executed by SS soldiers; the sixth victim was the county commissioner, who probably shot himself. In Burghausen SS soldiers killed three employees of the Wacker Chemical GmbH, who, together with others, were trying to protect the factory from an expected explosion. The priest and the teacher in Götting, who had raised a white-blue flag on the church tower, also became victims of SS officers. FAB sympathizers, who on May 3rd acted as parliament members and wanted to transfer the Tegernsee Valley to US divisions, were shot in Bad Wiessee by SS soldiers, even though they possessed permits. Two of them died from the wounds. Near Iffeldorf a disabled first lieutenant was executed because he had participated in a disarmament process. Near his corpse lay that of a Polish forced laborer, whose cause of death remains uncertain.

Map of the various related activities following the FAB announcements

Mathilde had to testify as witness in the proceedings against the Volkssturm men from the central ministry. Unfortunately, she had hardly been able to see anything from her cell. During the proceedings it was determined that a total of nine men had been shot either in the yard of the ministry or in the Perlach Forest after transport. The former governor Paul Giesler, who had ordered the actions, could no longer be placed on trial. He had taken his own life after fleeing to Berchtesgaden.

Similar to the accused in other proceedings, the Volkssturm men stated that they were merely following orders with these actions. All along the line, the proceedings had the same pattern: Whenever accusers and offenders could be identified, they all proved that they were only following orders. The judgments often turned out mild, and then after revision, the sentences were even reduced or changed to acquittal.

Berganger

A friend of Mathilde’s father served as priest for the Berganger parish near Glonn, about 25 miles southeast of Munich. In the early 1950s they touched on the topic of the Bavarian Freedom Initiative and its consequences. The priest mentioned that there was an incident in Berganger involving one death, however, he could not provide any details. The events were too close in time and the people involved were seen daily.

In 2011 Günter Staudter was working on the town chronicle for Berganger and stumbled on some clues. The folder of documents revealed the events in the following manner: The radio announcements by the FAB were also heard in Berganger. To prevent the Volkssturm men from defending the town, several men planned to disarm the lead teacher, who directed the Volkssturm unit. Four or five men from the village went to his house and demanded that he surrender the 40 rifles. The teacher refused and a fight ensued, probably because the men thought he was pulling out a pistol from his jacket. From behind a shot rang out. It was fired by the teacher’s daughter. Johann Huber, a farmer from the neighborhood, fell to the floor dead. The fighting continued until the soldiers called by the daughter forced the other insurgents to flee. They were able to hide in Berganger until the US troops arrived. In the court proceedings after the war (the records of which are no longer available) the teacher’s daughter stated that she only intended to give a warning shot. She was acquitted.

Leap in time – Retrospect

On May 17th 1985 an older Mathilde arrives at the Munich airport Riem. She thinks back on this day 40 years ago. The US military authorities had prohibited the activities of the FAB as well as the organization itself. Although several of them tried to hold the circle of activists together, most of them were busy with the challenges of the postwar times. Things were no different for her. Her employer, Radio München became Bavarian Radio in 1949. Mathilde had already left there some time earlier to return to her previous line of work in architecture. During her employment at the radio station she met Anselm Miller from New York. He had participated in the Normandy Operation Overlord. Due to his skill as amateur film-maker, he was assigned to the unit which filmed the liberation of the concentration camp in Dachau. His later duties at Radio München involving the re-education in the US occupation zone were influenced by what he saw there. He could not understand why the people, who had shown such cruelty, were not pursued more vigorously and properly convicted. There were many lesser injustices which sometimes drove him to despair on the job. Mathilde viewed the issues from a more indifferent perspective. Over the years she had witnessed what the NS regime had done to people. Anselm had a different opinion. He knew that Mathilde had barely survived while being held in the central ministry, even though this was at the end of the war. However, she recalled, she had only coincidentally stepped into the events with the FAB through her work at the interpreter unit. Yet, Anselm countered that she still had placed her life on the line by attempting to participate in the uprising against the Nazis. She could have just stayed at home in the safe apartment. They often spent the evening at the kitchen table discussing this issue. As the tensions between East and West continued, former Nazis were integrated back into German society even faster. Anselm anxiously followed the Nuremberg Trials, but was not at all satisfied with the judgments. Once he received the opportunity to leave the army, he chose to return to the USA.

Mathilde decided to accompany him, even though it was difficult for her to leave her parents and friends behind in Munich. Before departing she had the chance to meet some former colleagues from the FAB: Ottheinz was now legal advisor to the Bavarian Radio service, and Leo Heuwing had just started his career as architect. In 1956 he would become executive director of the Deutsches Museum, and Rupprecht Gerngross was working as a lawyer.

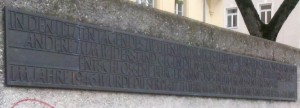

Now in 1985 she hoped to visit a few friends and see for herself the commemorative plaques at Münchner Freiheit. She had a bit of trouble finding the bronze, elongated panel at the end of the eastern wheelchair ramp. She then took the subway the three stops to Odeonsplatz. For the first time in 40 years she entered the building on Ludwig Street, where she had been incarcerated at the end of April 1945. Now it was home to the Ministry of Agriculture. The inner courtyard also displayed a stone panel to commemorate the victims of the uprising. Hesitantly she approached the gate through which one could look at the neighboring yard where several of the victims had been shot.

I will now say farewell…